Why do some ideas succeed while others fail?

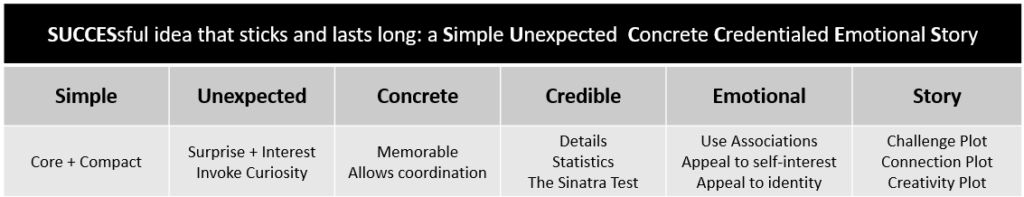

We have come across several urban legends that resonate with people though they are unbelievable and false, while some of the most potent transformational ideas are not even considered. The traditional belief is that successful communication requires getting the right people and setting the right context. But there is another factor that is key for an idea to become viral – “The Stickiness Factor” as explained by Malcom Gladwell in The Tipping Point. This blog is about a different book Made to Stick by Chip and Dan Heath, which identifies the traits that make ideas sticky and provides a checklist for creating a SUCCESsful idea: a Simple Unexpected Concrete Credentialed Emotional Story.

Simple: Great simple ideas have an elegance and a utility that make them function a lot like proverbs: short sentences (Compact) drawn from long experience (Core). Simple = Core + Compact

- Finding the core requires stripping down an idea to its most critical essence. To get to the core, we have start with weeding out the superfluous elements and eventually get down to the tougher part of eliminating ideas that may be really important but just aren’t the most important idea.

- Creating a compact message is the next step once the core is identified. Compactness is all about elegance, prioritization and being crisp. It should not result in dumbing down or shooting for the lowest common denominator to make things easy. Techniques like “inverted pyramid” used by journalists to present information in descending order of importance and “forced prioritization” limiting to just one thing, are helpful.

- A few examples of simple ideas that are compact while retaining the core idea:

- SouthWest Airlines tagline: THE low-fare airline.

- Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign lead: It’s the economy, stupid.

Unexpected: The first problem of communication is getting people’s attention. The most basic way to get someone’s attention is by breaking a pattern as humans adapt incredibly quickly to consistent patterns. For example, we quickly get used to certain sounds like that of our air-conditioner or ceiling fan and certain smells like a room freshener or candle, that we become consciously aware of these things only when something changes. To get people’s attention and keep it, naturally sticky ideas provoke two essential emotions: Surprise and Interest.

- Surprise gets our attention. Some naturally sticky ideas propose surprising “facts”. Like the statement “You use only 10% of your brain”.

- Interest keeps our attention. Interesting ideas like conspiracy theories or gossips makes us keep tab on developments thereby maintaining our interest over time.

- The Gap Theory of curiosity: Curiosity happens when we feel a gap in our knowledge and these gaps cause pain till they are filled. To leverage the gap theory, we sometimes have to set the context and give people enough backstory that they start to care about the gaps in their knowledge. Mystery novelists and crossword puzzle writers excel in this technique by setting some context and giving us clues that generate sufficient interest when curiosity takes over and propels us to finish!

Concrete: As we master a language, we use complex words and abstraction to make our point. When we deliver our beautiful abstract message, listeners admire our mastery over language and extensive vocabulary. However, abstraction makes it difficult to understand an idea and remember it. It also makes it harder to coordinate our activities with others, who may interpret the abstraction in different ways. Concreteness helps us avoid these problems:

- Concrete is memorable: When we are asked to remember how a beach feels, our sense memories are immediately evoked bringing back memories of the sight of sand and waves, smell of the ocean, sea breeze blowing across our face, etc. For a person who has not seen a beach at all, it is only the textbook definition of beach that comes to mind at best and cannot relate to it as well.

- Concrete allows coordination: Abstract statements can mean different things for different people. For example, a goal to manufacture “the best car” will mean top speed for a race driver while it will mean comfort and space for a person looking to drive his family of four for a picnic. So, making it concrete with tangible aspects like “the car that can comfortably accommodate a family of four along with ample space to carry picnic bags” will help effectively coordinate within a team and reduce scope for different interpretations.

Credible: People’s beliefs are based on years of trust built in family, personal experience, faith and authorities. However, we can’t always rely on these factors to vouch for our message. Most of the time our messages have to vouch for themselves and must have “internal credibility”, which can be obtained from three sources:

- Details: A person’s knowledge of details is often a good proxy for expertise. Vivid details shared along with the message will increase the credibility of the idea.

- Statistics are a good source of internal credibility when they are used to illustrate relationships. Using “human-scale principle” will make statistics more effective and allows people to bring their intuition to bear in assessing whether the content of the message is credible.

- The Sinatra Test: In Frank Sinatra’s classic “New York, New York”, he sings about starting a new life at New York City and the chorus declares, “If I can make it there, I will make it anywhere”. An example passes the Sinatra test when just that instance is enough to establish credibility in a given domain. For example, if you have driven on Indian roads, you can drive anywhere.

Emotional: Accidental mutation of human brain thousands of years back led to cognitive revolution resulting in agricultural, scientific and industrial revolutions through analytical thinking that set us apart from other animals. However, most of our actions are still driven by primitive emotions or feelings invoked by an event. As we prepare to communicate our idea, it will help to remember that using statistics or science to make our point shifts people into a more analytical frame of mind. When people think analytically, they are less likely to think emotionally that makes them care for something. There are three strategies for making people care:

- Using associations (or avoiding them as the case may be): Piggybacking strategy associating ideas with emotions that already exist.

- Appealing to self-interest: Highlighting what is in it for oneself is a powerful way of engaging people with an idea.

- Appealing to identity: In some cases, going beyond self-interest and appealing to an identity that people care about will be impactful.

Stories: There are numerous books highlighting why stories are the most effective means of communicating messages at work and I have a blogpost on one of them. “Made to stick” highlights that stories cause mental simulation that evokes the same modules of the brain that are evoked in real physical activity. So, while mental simulation is not as good as doing something, it is the next best thing. There are three basic plots that can be used to make our ideas stick:

- The Challenge Plot: Obstacles seem daunting to the protagonist and the triumph of will power over adversity inspires us to act.

- The Connection Plot: These are about our relationships with other people and will be a good way to build relationships.

- The Creativity Plot: Involves someone making a mental breakthrough, solving a long standing puzzle or attacking a problem in an innovative way.

To summarize, for an idea to stick and be useful for a long time, it has to make the audience:

- Pay attention

- Understand and remember it

- Agree / Believe

- Care

- Be able to act on it