Can you remember instances when you decided to pursue a course of action that went against your professional training?

Have you wondered why leaders at times make silly mistakes by ignoring the obvious?

The question when we look back at such incidents invariably is: How can a professional with such established reputation and years of experience do this?

Leaders have to make decisions all the time based on available data and with no guarantee of success. Though they typically have the best interests of their organization in mind, sometimes things do go wrong and posterity can attribute at least some of the failures to past “irrational” decisions. It is usually easy for people to provide elaborate commentary on poor results with hindsight bias. Does this mean all leaders are doomed to be criticized in the future? Brafman Ori’s book “Sway: The Irresistible Pull of Irrational Behaviour” can help leaders deal with this occupational hazard during decision making by being aware of potential pitfalls due to certain psychological undercurrents: loss-aversion, swamp-of-commitment, value-attribution, diagnosis-bias, self-perpetuation, fairness-of-process and group-conformity.

The first time I came across the concept of irrational behavior was in the Dan Ariely’s book “Predictably Irrational” several years back. It was before I started blogging and when I was still reading non-fiction for fun rather than leadership insights. Brafman Ori has taken it to the next level by explaining the reasons behind these irrational behaviors and also shares some practices that can help us avoid falling into the trap.

History is filled with numerous instances of top-notch, award-winning professionals making a choice that contradicted their years of training resulting in disastrous outcomes as they swayed from the logical path. This book explores some of the psychological forces that derail rational thinking: how they creep upon us, when are we most vulnerable to them and why don’t we realize that we are getting swayed. By better understanding the seductive pull of these forces, we will be less likely to fall victim to them in the future.

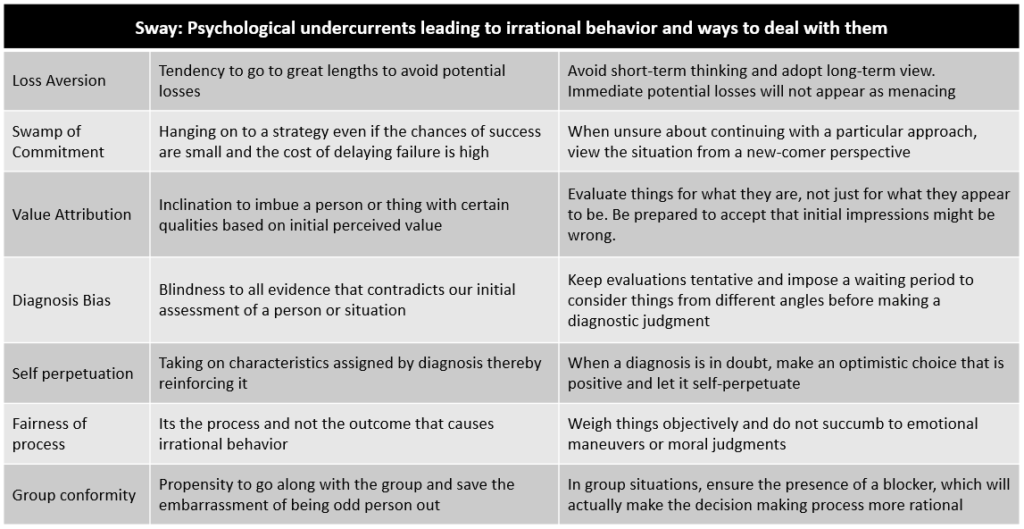

Loss Aversion – tendency to go to great lengths to avoid potential losses: Human mind naturally experiences the pain associated with a loss much more vividly than it does the joy of experiencing a gain. This results in our overreacting to perceived losses for no apparent logical reason. The more meaningful a potential loss is, the more loss averse we become and get swept into an irrational decision. Some examples of this behavior are people subscribing to expensive “unlimited” phone or internet plans to avoid perceived loss associated with pay-as-you-go, investors in financial markets concentrating on avoiding losses rather than focusing on maximizing their gains, etc.

Swamp of Commitment – hanging on to a strategy even if the chances of success are small and the cost of delaying failure is high: History is filled with stories of civilizations and companies vanishing by sticking to a committed path even after realizing the need to change. It is also what leads a gambler or investor to chasing losses. Loss aversion and commitment have powerful effect on their own. But when they both combine, it becomes that much harder to break free and do something different.

Value Attribution – inclination to imbue a person or thing with certain qualities based on initial perceived value: From our childhood, we form perceptions about value. For example – premium branded products are preferred over regular ones even if packaging is all that is different, a lawyer is trusted more when he shows up wearing a fancy suit. We have mental models of how a top investment banker or computer geek or a seasoned politician will look like. Anyone who does not fit the stereotype finds it difficult to gain acceptance.

Diagnosis Bias – blindness to all evidence that contradicts our initial assessment of a person or situation: The proverb “The first impression is the best impression” is based on this psychological undercurrent. After all, the first impression might have occurred under exceptionally fortunate or unfortunate circumstances.

Self perpetuation – taking on characteristics assigned by diagnosis thereby reinforcing it: This is also called self-fulfilling prophecy or chameleon effect. When we brand or label people, they take on the characteristics of the diagnosis. It is also called Pygmalion effect when a positive trait is assumed and Golem effect in case of negative traits.

Fairness – its the process and not the outcome that causes irrational behavior: We expect procedural justice from people we deal with, which is perceived fairness of the process rather than just a fair outcome. For example, we consider a car salesman to be fair when he explains the reasons why the original price is worth every penny rather than another who gives an easy 10% discount without spending any effort to explain why this is the best possible deal. In the second case, we leave with the question of why only 10%, did the salesman really give me the best deal or did I overpay? To avoid this fairness dilemma, managers are asked to put greater effort, energy, investment and patience into nurturing relationships.

Group conformity – propensity to go along with the group and save the embarrassment of being odd person out: Regardless of how independent minded and steadfast people are, it is common for people to align with a group instead of voicing an unpopular viewpoint due to fear that others will doubt their intelligence, taste or competence. For a decision to be made by comprehensively considering all possibilities, it is important for the discussion to include initiators, blockers, supporters and observers. It might be frustrating to encounter blockers for what might appear to be an obvious course of action, but their opinions are absolutely essential to keeping groups balanced and hold back irrational behavior.

If this book were a movie, the first 90% is an intriguing build-up and the Epilogue is a fitting fast-paced climax where Brafman Ori gives us some invaluable suggestions on ways to avoid these pitfalls, some of them below:

- Our natural tendency to avoid the pain of loss is most likely to distort our thinking when we place too much importance on short-term goals. When we adopt the long view, immediate potential losses don’t seem as menacing.

- When we find ourselves unsure about whether or not to continue a particular approach, it is useful to ask – “If I were just arriving on the scene and were given the choice to either jump into this project as it stands now or pass on it, would I choose to jump in?” If the answer is no, then chances are we have been swayed by the hidden force of commitment.

- The best strategy for dealing with the distorted thinking that can result from value attribution is to be mindful and observe things for what they are, not just for what they appear to be. You have to be prepared to accept that your initial impressions might be wrong.

- “Propositional thinking” is all about keeping evaluations tentative instead of certain, learning to be comfortable with complex, sometimes contradictory information and taking your time and considering things from different angles before coming to a conclusion. Net-net, a self-imposed waiting period before making a diagnostic judgment can help avoid diagnostic bias.

- One way to counter fairness sway is to try to weigh things objectively and not succumb to emotional maneuvers or moral judgments.

- When we make decisions or take actions that will affect others, keeping them involved will help ensure that they feel the process is fair.

- Just as communicating our process is important, so is giving voice to the dissenter. In group situations, the presence of a blocker can actually make the decision making process more rational and less likely to go off the track.

The ability to think has set humans apart from other animals and become all-conquering species. At the same time, our natural decision making machinery has limitations that leads us to being swayed at times by factors that have nothing to do with logic or reason. This book will help us recognize and understand the hidden world of sways, and learn to weaken their influence on our thinking process.